The following was written by Maryam Sy, a translator, interpreter, and community leader who also serves as the Organizing Director of the Ohio Immigrant Alliance. Read the original post here. Learn more about Sy Translation and Consulting here.

In November 2024, I attended an immigration hearing at the Cleveland, Ohio Immigration Court. The young man seeking asylum, the “respondent” as the judge called him, is from West Africa and was present in court with his attorney. I’ve only been to the Cleveland immigration Court a few times. The weight of the decisions made there can have such significant effects on people’s lives, that I always go with a sense of apprehension, feeling butterflies in my stomach. I guess my trauma with immigration is from personal experience and from the experience my husband had to endure as a Black Mauritanian man.

Work with the Ohio Immigrant Alliance (OHIA)

During our work on the #ReuniteUS project at the OHIA, we interviewed over 200 people, many of whom were from the Halpoular (also spelled “Haalpulaar”) ethnicity (1), originally from Mauritania. The project focused on deported people and our advocacy around it was to get President Joe Biden’s administration to bring people who were unfairly deported back home to the U.S. Over the course of the interviews we conducted, people shared the challenges they faced during their immigration court hearings, particularly with the language barrier. Many described how interpreters were often not familiar with Mauritania’s Poulaar (also spelled “Pulaar”), which is also sometimes referred to as Fulani, especially since it is a language that is spoken across 18 different countries in Africa, with significant variations.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, many Black Mauritanian asylum seekers had their cases denied by immigration judges. They explained to us how they felt unheard, disrespected, and ashamed in court. They thought their cases didn’t matter to the immigration court, and felt like their experiences were not considered credible despite their physical and emotional scars. The courts often accused them of lying about what happened to them in their country. Most of the Mauritanians who fled in the late 1990s were Black Mauritanians, leaving their country because of racial persecution, slavery, people disappearing, and even death. Those issues are still happening today in modern Mauritania and the country conditions are worse for Black Mauritanians than other ethnic groups.

Who Are the Poulaar Speakers? The Halpoular

The Halpoular people, or Toucouleur as the French call them, are known to be keepers of their culture by preserving their authenticity throughout the centuries. The Toucouleur Empire was founded by my ancestor, Cheikh Oumar Foutiyou Tall who led the resistance against the French in the mid-19th century. The Poulaar language is a central part of their identity. Many Halpoular families prioritize teaching their children the language fluently, as it is seen as a key element of their cultural heritage and connection to their ancestors, actively preserving and protecting their culture, passing it down through generations via language, oral traditions, religious practices, and social customs. Despite the challenges posed by modernity and migration, they continue to maintain a strong sense of cultural identity.

In the late 1960s, my father immigrated to France, and my mother followed him in the mid-1970s. They were determined that we learned Pulaar fluently before teaching us French, and I’ve continued this tradition with my own children here in the United States. We were fortunate to grow up in a multilingual household, where exposure to several languages was a natural part of our daily lives.

Pending Mauritanian Cases in Ohio

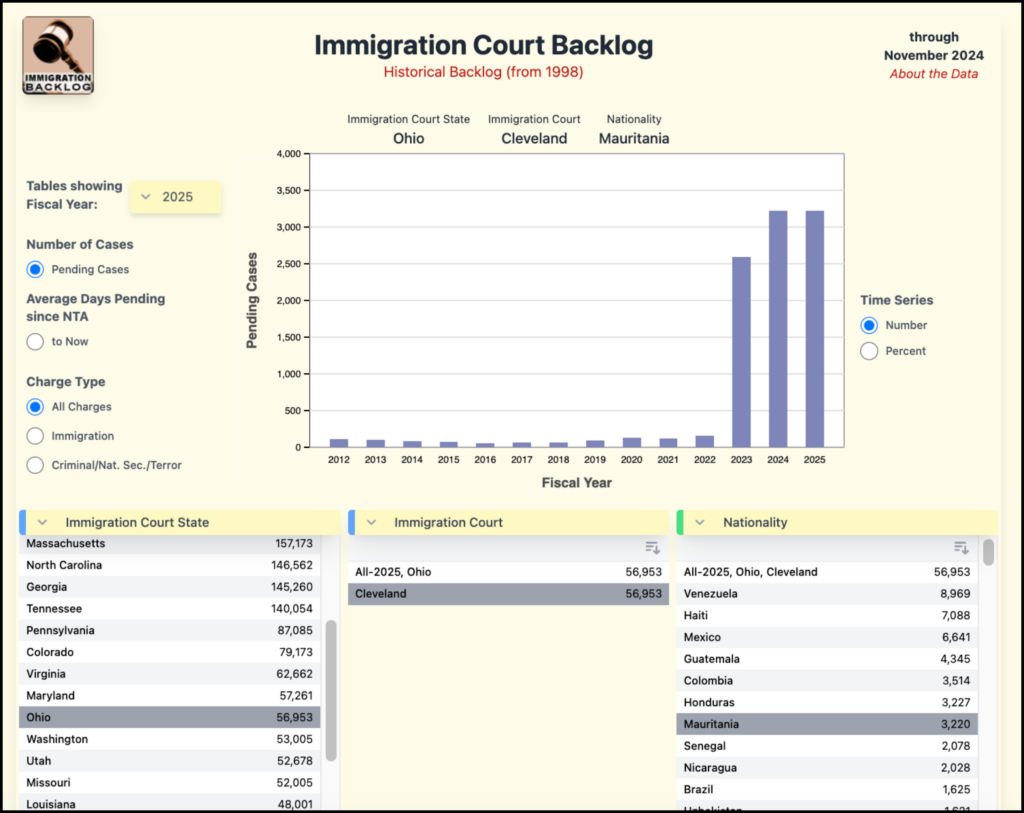

According to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), 88% of asylum cases decided in the Cleveland Immigration Court between October 2020 and September 2021 were denied. TRAC reports that more than 3,000 cases pending in the Cleveland Immigration Court in 2024 involve Mauritanian nationals, and over 2,000 cases involve Senegalese nationals.

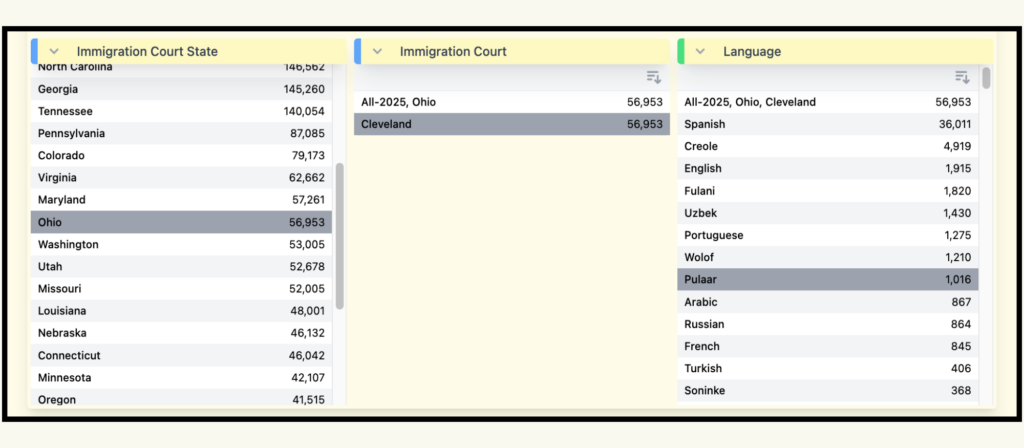

There are over 5,000 Mauritanian and Senegalese cases pending in the Cleveland Immigration Court. People from Mauritania and Senegal are usually multilingual, and may speak French, Fulani/Pulaar, English, Wolof, Soninke, Bambara, Arabic, Hassaniya and other languages.

According to government data reported by TRAC, the Cleveland Immigration Court has 1,820 cases pending involving “Fulani” speakers and 1,016 cases involving “Pulaar” speakers. “Fulani” is the fourth most-common language spoken by respondents appearing in this court, after Spanish, Creole, and English, and “Pulaar” is the eight most-common language, following Uzbek, Portuguese, and Wolof. It is unclear how the government defines “Fulani” and “Pulaar” in its data. Judges have not demonstrated an understanding about the difference between Mauritanian/Senegalese Fulani (Pulaar) and other dialects.

Screenshot of government data on languages used in the Cleveland Immigration Court (from TRAC)

Let’s go back to the story, shall we?

As I was sitting in court and listening to the interpreter, I noticed that his Poulaar was of the correct dialect, meaning that both the “respondent” and I were able to understand him. But as soon as the Immigration Judge (IJ) started talking, the interpreter was having difficulties translating properly what the IJ was saying. The interpreter asked the judge to repeat himself multiple times, and he was clearly having difficulty translating the vocabulary of the court.

For example, two key pieces of information that the interpreter was having difficulties translating were the Notice to Appear (NTA), which is the formal document that starts removal proceedings against a foreign person, and information about Removal Proceedings, which happens when the government asserts that an individual doesn’t have a valid immigration status and therefore must appear before an immigration judge to resolve their case, with either a grant of immigration relief, closure of the case, or issuance of a deportation (removal) order.

However, there is no direct equivalent for “Notice to Appear” or “NTA” in the Poulaar language. In French, a Notice To Appear would mean “Avis de Comparution” (signifying that the person has to present himself in front of a court). While the interpreter appeared to understand the concept of an NTA, he was unable to accurately translate the meaning of it or provide a clear explanation to the respondent.

There is also no textual definition of “Removal Proceedings” in Poulaar. When the interpreter was translating, he said in Poulaar “Nowtugol ma,” which means: “your deportation.” It was confusing to the “respondent” and quite frankly, to me as well. In my opinion, he could’ve used an expression like “immigration court hearing,” which in Pulaar is “ñaaworé ma imigarasion.”

Read “Scarred, Then Barred: Immigration Courts Harm Black Mauritanian Refugees” for more examples of how immigration courts have failed to provide accurate language interpretation for Fulani/Pulaar speakers, with negative impacts on their cases and lives.

Thank goodness this particular hearing was a Master Calendar Hearing (2) rather than an individual hearing, meaning that no decisions about the outcome of the case would be made on that day. In the United States, it is difficult for the court to properly evaluate an interpreter who speaks a “rare language” (3). There is no formal written or oral exam for languages like Poular, so interpreters often become certified in more widely-spoken languages, such as French, and simply add rare languages to their credentials. As a result, without a way to assess their proficiency in English or the legal nuances of the court system, situations like the one I witnessed in court arise too many times.

Solutions?

I asked the question to an immigration attorney practicing in Ohio. He wrote: “One of the problems is that the Department of Justice contracts with private companies to provide interpreters, and so many federal contracts go to the lowest bidder. In this case the language contractor is SOSi. One solution would be to require anyone who interprets in immigration court to be certified to interpret in regular federal court, but that would create a huge problem for the agency because there aren’t enough federally certified interpreters. Still, language services are too important to be contracted out to the lowest bidder, and a lot more needs to be done to ensure quality control.”

I couldn’t agree more on the importance of quality control in these situations. It’s alarming that cost considerations might compromise the integrity of court proceedings. Moreover, this issue extends far beyond immigration, affecting the medical field as well. Effective communication between patients and medical professionals is crucial, and language barriers can have severe consequences. Ensuring accurate interpretation services is vital in both courts and hospitals, as the decisions made can have life-altering implications for individuals. It’s essential that we prioritize the provision of high-quality interpretation services to safeguard the rights and well-being of all individuals, regardless of their linguistic background.

Sources